By Julie Mountcastle, Head of School and Chief Innovator

Head of School Blog

Better Together, and the Art of Collaboration at Slate School

Collaboration: the action of working with someone to produce or create something toward a common goal or objective.

cooperation, alliance, partnership, participation, combination, association, concert, teamwork, joint effort, working together, coopetition

The definitions are simple. As simple as it is to see the value of collaboration, the act of true collaboration is infinitely complex. I have seen it fail many times and still feel sure that I haven't seen it fail for the last time. This doesn't discourage me though. I always learn something from these collapses that makes me a better learner and partner. But first, let's just think about why this endeavor is worth all of the trouble. I think that the best way to consider this is to imagine a world without the sharing that has brought some of the greatest advances in whatever field you'd care to consider. For example, we might never have — or at least been delayed in — the invention of flying, or understanding the structure of DNA, or listening to “Let it Be from The Beatles,” and surfing the Internet, just to name a few. There would also be much less joy in the workplace, as well as many, many, more ideas that would have just remained as ideas circling around in their creator's mind.

At Slate School, collaboration is more than just ideas that lead to the creating of something, although we do create things here. It is more about the realizing of personal potential through learning and collaborating with others. And not just learning from like-sized colleagues, but also — and maybe even more often — from children of all ages. I'll never forget my initial delight at looking at the cover of the book All I Really Need To Know I Learned in Kindergarten, only to be profoundly disappointed to discover that the majority of the discoveries cited were taught by the teacher. This totally misses the mark for me. As a Kindergarten teacher, I felt and continue to feel that the discoveries came from the kindergarteners, not the teacher. Children have much greater intuitive understanding of the world than we do, and when we really collaborate with them and actually listen to them — and work to create some thing or some new understanding with them — we come to very interesting, innovative, and often thrilling discoveries.

Working with children and other educators has been a great joy in my life. I knew that I needed this kind of work long before I became a professional educator. I often laughingly say that I thought that musical theatre was the most collaborative art form, until I became a teacher. It had seemed reasonable. There were sets and costumes to design and build, scripts to write and rewrite, music to compose and orchestrate, directors to hire and time given for them to establish a vision for the production, actors to hire and rehearse, lighting and soundscapes to design and engineer, musicians to hire and rehearse, and all of this before the nightly collaboration with the audience. It still seems overwhelming to think of the enormity of all of that, so lovingly tucked into the past. What I have come to understand is that as educators, we are working everyday with as many as 20 playwrights, each of them with strong and worthy ideas of their own story, through which we weave the questions that prepare them for our complex world. We watch for our cues to ask or notice in order to encourage the children to extend their wonder and imagine their answers. The script is never the same. In the theatre, there was usually a speech given by the director after the show had been in previews and was ready to open. We called it the “Birdseye” talk, because after that the show was “frozen,” and the performance was to remain the same every night until we closed. Thankfully there is no such conversation in a child centered, curiosity-based school. I now even question the wisdom of that concept in the theatre. How foolish to depend on the creativity of every human engaged in the endeavor only until it meets the expectations, and then ask all of those creators to stop their imagining and to just repeat previous revelations for the eternity of the production. In a school, or at least in our school, we rely on the collaboration of all participants every day. We watch the children in our own classes and discuss common observations. We take time to observe learners in the other environments, as well as each other in our practice. These observations are the basis for conversations that are critical to the growing we all hope to do in the course of our careers and as humans.

I should take a moment here to talk about the environment that must fully be in place for these conversations to be truly fruitful. Talking honestly about areas where we hope to grow can be uncomfortable in even the most trusted circles, so this is certainly something to consider before engaging in these conversations. Developing this environment is worth it though, as creating a trust-filled, risk-friendly environment does so much more for a school than just engender good dialogue, and this work is also best done in the spirit of collaboration.

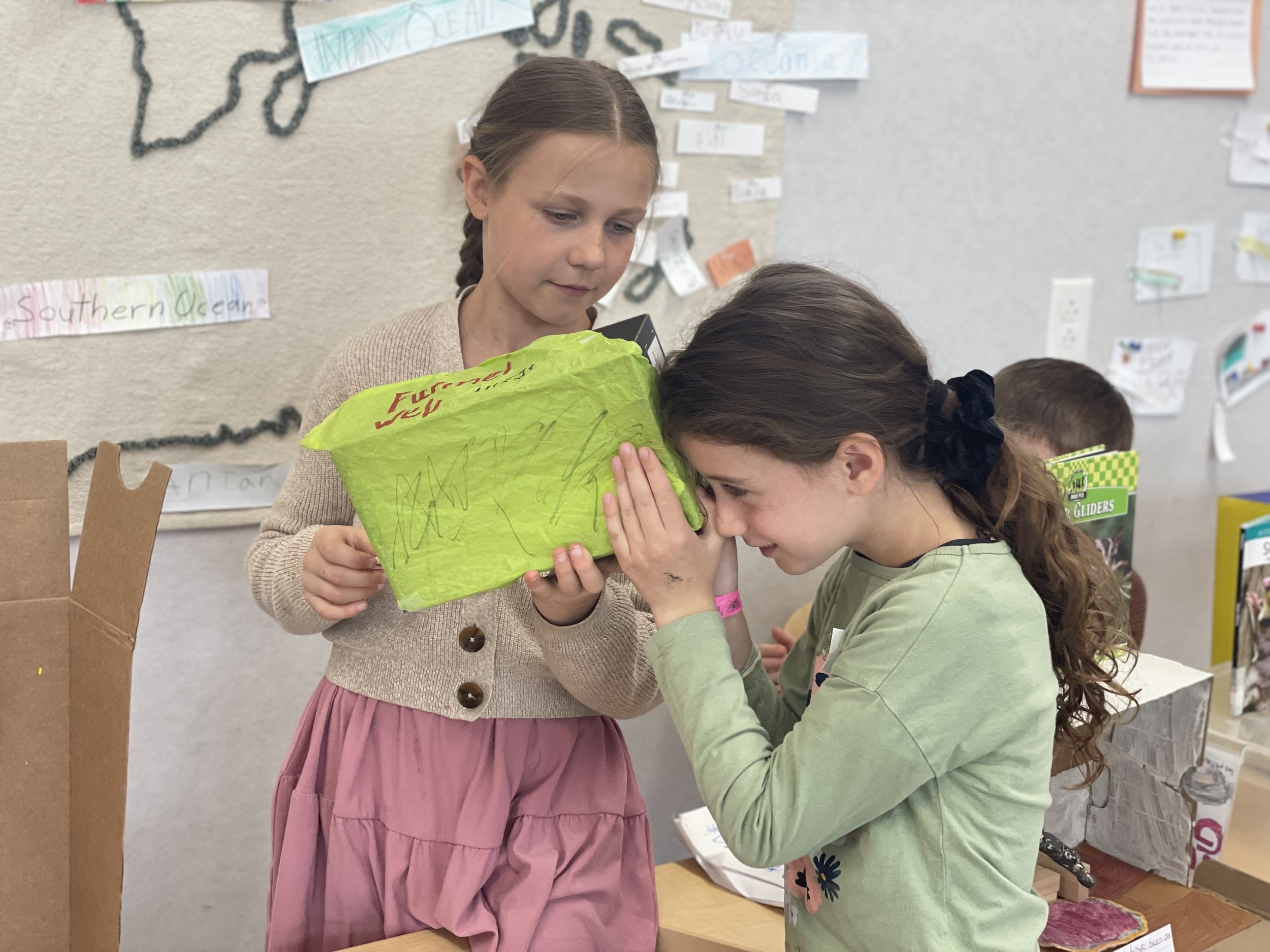

At Slate School, collaboration takes many forms. It involves the observations and conversations described above, but it is also the recognition of each other’s talents and lenses. When we plan at Slate School, for example, the whole faculty uses a single shared document. We dream over the weekend about the possibilities for learning that the children have initiated over the past week. We all have our own text colors, and we expect and hope for a fully collaborative response to our wonderings. These thoughts often lead us to contemplate exciting offerings for the children to explore and many options for connecting with elements of our curriculum. The options are pivotal because we want to always follow the curiosity of the child, bringing forward understandings for the child to discover, without planning an exact path that limits the child to that path. This is not work for the faint of heart, and we rely on our colleagues to keep us accountable for this kind of teaching. We also recognize the talents of our fellow educators and learners by asking them to teach all of us, whether it be our Environmentalist teaching about the garden planning, or a 1st Grade student teaching the whole community about the life cycle of the Woolly Bear Caterpillar. In fact, identifying growing expertise in the community is a powerful motivation for continued deeper learning. We assume that everyone will have their own passions and that we can look to each other for help whenever we feel the need. This frees all of us up to work on what we love. I hope it is clear that I am speaking of the entire community, from Head of School to the Kindergarten student, and that as learners, there is no hierarchy. There are many things I know less about than any number of the children in the community. Age and education level do not grant us universal knowledge. And isn’t that a glorious thought? We all still have as much to learn as anyone else. How, then, could we ever survive without collaborating?